Getting into the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) from Russia is not entirely easy. After several aborted attempts, where our Russian contacts show an almost embarrassing concern for my safety – the fighting has intensified in the last few days – I am finally able to cross the border on a bus filled with volunteers on their way to Donetsk. By this time my interpreter has backed out after the failed attempts to find a safe road the night before, and no one in the bus speaks more than a few phrases of English.

When the bus stops at the separatist-controlled border outpost at Kuybushevo, the volunteers are allowed forward for inspection in small groups at a time, and I take the opportunity to communicate with my fellow-passengers using a mix of English, German, Swedish and gestures. Every now and then I can hear artillery firing somewhere along the border, but the guns are out of viewing distance.

The volunteers are using code names. The Ukrainian state has classified the entire DPR as a terrorist organization, thus making it punishable to assist it, with or without weapon in hand.

Most of the volunteers on the bus are males in their twenties or thirties, but there are also a few women and older men among them. Some are there to do humanitarian work for the civilian population, others to work for the administration; most probably want to join the DPR:s armed forces.

For obvious reasons, Russians form the overwhelming majority of those willing to join the Russian-speaking separatists, although there are also volunteers from Western Europe and other countries.

All the volunteers on my bus are Russian speakers, but at least two of them are from Kazakhstan. One of those, “Alexander”, is blond with European features, and I learn that his grandfather was from Ukraine and fought against the fascists during WWII. He says he is there to defend Russian civilization from American aggression and fascism. The other one is a short young man with an Asian appearance, who has acquired some knowledge of Scandinavia’s people and culture from the videogame Skyrim.

– Shvedsky? Ah, Skyrim… Nords… ”Draaaaagoooon!”, he says while mimicking a Nord (the game’s equivalent to Nordic people) throwing his spear at a dragon.

He and several others are also familiar with the Swedish warrior king Charles XII, however, and seem to regard him as a worthy opponent of Peter the Great. Three times during my visit, when someone learns that I am Swedish, they mention “Poltava”, the battle where Sweden finally lost the war. Each time, I counter with “Narva” (where Swedish Carolingians beat a much larger Russian army), which is met with some amusement.

The volunteer with the best knowledge of English, which is not saying a lot, goes by the code name “Admin” and is 52 years old. As far as I can understand, he used to work in computer security for the Donetsk administration, and is now returning to do the same for the DPR. Several of the volunteers are from the eastern parts of Ukraine – Novorossiya, New Russia, as they call it nowadays – and are returning home to join the fight against the Kiev regime. “Taur”, a 46 year old man from Lugansk, explains with some help from Admin that his mother has been killed by the Kiev fascists and that he wants to help drive them back.

– No pasarán, he exclaims with his fist clenched. An expression meaning “they shall not pass”, dating back to the Spanish civil war. In Sweden it is mostly associated with left-wing extremists.

By this time, I am already getting used to the different political roles in Russia and New Russia as compared to Sweden. The Russian notions of anti-fascism are not at all associated with fighting for mass immigration, gay parades or feminism, but rather with Russian patriotism and a certain amount of Soviet nostalgia. Several times I hear antifascist fighters expressing opinions about the aforementioned phenomena which would probably mark them as “right-wing extremists” according to Sweden’s leftist and liberal newspapers. Similarly, the German journalist and editor Manuel Ochsenreiter, who I spoke to before my visit, is regarded as a true antifascist in Russia, while he has been accused of “right-wing extremism” in Germany.

Like I said, one gets used to the differences.

Finally allowed to walk up to the border outpost, the guards are obviously taking a special interest in me as a Western European with a journalist visa. An English-speaking officer is called on the phone to communicate with me. Why do I want to visit the war zone? What people have I been contacting before my journey? And then the question which makes me sweat a little: “Why have you chosen this road into Donetsk? There are safer passages!”

I wish I had a picture of my face at that moment.

After answering the officer’s questions, apparently in a satisfactory way, I am finally let through, almost three hours after the bus stopped on the other side of the outpost. I take a position in the gangway of the bus, put on my bulletproof vest, and hang my camera around my neck.

Burnt-out vehicles litter the side of the road, but after an uneventful hour the bus enters Donetsk, which immediately strikes me as a quite beautiful city.

A short while later, I am at the news agency of Novorossiya, shaking hands with Georgy Morozov who has agreed to help me.

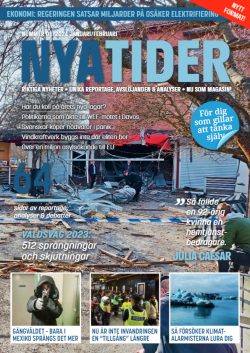

Five minutes after we meet, Georgy’s phone rings. Civilian areas have been hit by artillery and he is tasked with photographing the devastation. I tag along for what is for him just another day at work.

– One gets used to it, he says.

The residents of Donetsk have gotten used to waking up to the sound of artillery since Kiev’s forces reached the city’s outskirts. Another two or three civilians were killed in another attack the same morning.

An hour after having arrived in Donetsk, I have already taken pictures of several civilian buildings that have been shelled by artillery. After photographing a destroyed museum, me and Georgy are walking around the big football arena which was hit the same morning.

Before we have reached the damaged part of the arena, the booming sound of artillery is heard behind a ridge some kilometres away. No one around me ducks for cover, but everyone gets very tense and listens carefully. After a few seconds, the rumbling sound of the shells striking their targets is heard, again some kilometres away but in an area diagonally behind us.

Georgy starts speaking to a grey-haired militiaman in his sixties, then he gets a phone call and we rush to the car.

Traffic rules are no longer enforced in the besieged city, and after an extremely fast drive we arrive in a neighbourhood which has just been shelled, and I find myself looking down on a ten-year-old girl whose body is not yet cold. Her parents lie nearby, also with pieces of cloth covering their faces. Only later I learn that she had a little sister who died in the ambulance from her injuries.

I ask for the girl’s name, and a neighbour tells me she was called Christina.

Christina’s grandfather sits on a wooden bench a few metres from her lifeless body, obviously in a state of shock. He mutters that the family had stayed in Donetsk for his sake instead of fleeing, because of his poor health. Now he is the only one left.

A neighbour sobs uncontrollably as he tells us what happened. The family was out in the yard getting some fresh air on this hot Saturday afternoon, when the shells started raining down. They ran towards the house to get cover, but did not make it in time.

Constant shelling

The residents of Donetsk have gotten used to waking up to the sound of artillery since Kiev’s forces reached the city’s outskirts. Another two or three civilians were killed in another attack the same morning. After Kiev announced their offensive on July 10, aimed at retaking the city before Ukraine’s day of independence, hundreds of civilians have been killed.

– I can hardly remember what it’s like to go to bed knowing that you will wake up the next morning, says Anita, a young woman working at the news office who is assigned as my interpreter the day after.

But one gets used to that as well.

Anita’s neighbourhood has been shelled several times, and she is now living in a hotel in an area which is not attacked as often.

– It’s like this every fucking day here in Donetsk. I had enough of this shit already in Slavyansk, comments a young DPR soldier as the distant rumbling of artillery is heard for the fifth or sixth time on Sunday, Ukraine’s day of independence. The young man surprises me by speaking excellent German and very decent English, and explains that he has lived in Germany for several years but has returned to fight for his people. I would have liked to speak to him some more, not least about the militia’s dramatic breakout from Slavyansk, but he is only on a short smoke break and leaves. I see him briefly again next morning when he is going away on a mission, and in retrospect I assume he was going to participate in the big offensive that the separatist forces launched on the same day.

Many of Donetsk’s residents bear witness to Kiev’s artillery firing at civilian areas. When I and Georgy are walking through the apartment block next to the one where Christina and her family was killed, we are called from a balcony by 57-year-old Vladimir, who is holding a piece of shrapnel that just went through his kitchen window. After ascending the stairs to his apartment, we observe that both he and his wife have narrowly escaped serious injury or death – one shrapnel has gone through the balcony wall and the window into the living room, where Vladimir was sitting, and one through the kitchen window where his wife was standing. Both of them were only a few decimetres from being hit.

– I hope you’ll ask Obama why he started all of this, Vladimir says, apparently more angry than afraid.

– No pasarán, he exclaims and clenches his fist when we go back down the stairs.

Propaganda lies

During my brief visit in Donetsk, I see numerous civilian buildings that have been hit by artillery. Perhaps more revealing, I see no cases at all where military targets have been hit. Neither have any of the journalists I meet in the city or have contacted afterwards been aware of any such cases. The shelling seems to be either completely random, or even deliberately targeting civilian areas. In most cases, no military targets are even anywhere near the sites that have been hit. The only apparent reason for the attacks seems to be to cause misery and fear among the Russian-speaking population, making them flee the city.

That method of warfare is usually referred to as ethnic cleansing, but no Swedish media has used that word, even though the UN has stated that close to one million people have fled across the border to Russia.

I should also note that I could not see one shred of evidence for the oft-repeated claim that separatist militants entrench themselves in civilian apartments, and that the civilian victims are therefore collateral damage for which the separatists are to blame. Of course, I cannot exclude that such things may possibly have occurred, at some other time and place, during the months of conflict, but if so, that seems a flimsy excuse for what is happening in Donetsk.

If one is to believe the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine (NSDC), a state advisory agency working for president Petro Poroshenko, I have actually seen several examples of “terrorists” targeting civilians with their artillery – in areas which they themselves control. Some of the council’s propaganda claims are so outrageous that Ukraine’s larger English-language media refrain from publishing them, but they are published in Russian and Ukrainian and linked from various Twitter accounts.

Among other things, it is claimed that it was not Kiev’s troops but the “terrorists” who fired upon both the museum and the arena I visited only hours after they had been hit, in the middle of the city under separatist control. Before that, the NSDC claims according to Ukrainian media, the “terrorists” had been threatening the museum staff, robbing them of valuable paintings. It hardly needs to be stated that I saw nothing that gives the slightest credibility to these claims.

While revisiting the Novorossiya news agency in central Donetsk, I tell Anita to ask the staff why the pro-Russian separatists are so stupid that they keep firing at their own buildings, a question that causes everyone to laugh.

– Well, you know, it gets so boring here and we must find something to do once in a while, says Anita herself with a wry smile, causing a new round of laughs when she translates into Russian.

At the news agency in Donetsk they may laugh at the most outrageous propaganda claims, but in Kiev, where fourteen Russian-language media have now been banned by the authorities, one can assume that many people actually believe them. Curiously, not even the most obvious lies are exposed by Western media, who instead tell us that “Kiev and the pro-Russian separatists blame each other” for this or that incident.

The image being painted of the DPR militia by Kiev-loyal media and in particular the NSDC – and which to some extent has also left its mark in Western media – is basically one of a bunch of stupid, cowardly and cruel brigands, holding the civilian population hostage while alternately blowing them up and robbing them. Admittedly, my visit to Donetsk is brief, intense and does not leave much time for investigative journalism, but I simply don’t see anything that would corroborate that image, while I see many things that contradict it. Some citizens are enthusiastically behind the separatist militias, others are uninvolved, and there is of course the occasional Kiev-loyal resident – but I see nothing that would indicate the militiamen are striking terror into the population. Certainly, no one would dare flaunting the Ukrainian flag in Donetsk these days, but the same thing can be said for waving the DPR flag in Kiev, or showing off the orange/black band that some use to signify their support for the People’s Republic.

When several militiamen walk into a store on the morning of my departure back to Russia, I make sure to keep my eyes open for any signs that the shop assistants are feeling threatened or are expecting to be robbed, but on the contrary, the separatist fighters are greeted with warm smiles, chat amicably with the two ladies behind the counter, and pay for themselves before leaving.

After an hour-long, bumpy ride in a bus whose shock absorbers have probably been dead since the Soviet era, I am once again at the outpost bordering Russia. A long and nervous wait ensues as the DPR soldiers go through the over a thousand photos on my camera, laptop and extra memory card, and I draw a sigh of relief when I’m told they have only erased a handful of pictures that show the faces of militiamen who have not agreed to have their picture taken.

Monday at noon, I once again tread my feet on Russian soil and head towards the refugee camps around the Russian city that bears the same name as the one I just left: Donetsk. More about that in our next issue.

On the same day I leave Donetsk, the pro-Russian forces launch a major offensive that turns the tide of the war. One week later, when I talk to Anita over Skype, the artillery is silent in Donetsk.

How long that lasts remains to be seen.

Note: After the article was first printed, Donetsk has once again come under fire.